Connect Four in Elixir (Part 1)

After watching the Erlang Solutions webinar on game logic in Elixir with Torben Hoffmann and looking through the Acquirex code, I thought I would try something similar. Let’s take a look at the Connect Four game, which involves dropping colored pieces into the top of a 7-column, 6-row vertically suspended grid, and see how it might be done in Elixir.

I worked on the Connect Four logic last year in Ruby and then started on it in JavaScript when I was thinking of attending Hacker School (now Recurse Center) and needed some code for the interview.

My Elixir knowledge is limited at this point. I’ve read books and documentation, typed in lots of examples, and solved a few exercises on my own, but I don’t immediately know what language constructs to use to solve an arbitrary problem. Going into this I think I should default to creating a process for most things, and keep an eye out for places that pattern matching and recursion might be used to solve a problem.

First Version

My first attempt involved generating a project with a supervision tree and then adding in some modules like “Game” and “Player” and “Board” and “Space”. I just made them Agents as I knew they would need to hold some state, and I had no reason to pick anything else.

Then I got stuck trying to figure out how to talk to them. When the children get started, how do I find the process IDs? Am I supposed to store those? Can I look them up somehow?

I asked on Slack and was pointed to gproc which is a generic process registry. Interesting (and it is used in the Acquirex code) but it seems like overkill here. I learned about registered names for processes.

Moving on to sending messages to those processes… well, they’re Agents. They hold state. They don’t listen for messages. Which told me that they ought to be GenServers instead!

I switched most of them over. So now I can start them all up and they look very pretty in the Observer… but they don’t do anything. How do you begin the game? Should it prompt for the player name? Ask for a move? If so, which process does that?

I went back to Acquirex and looked around, and figured out that you need to Acquirex.Player_Supervisor.new_player(:wendy) and then Acquirex.Game.begin … then what? Someone pointed out the test that serves as a usage example.

So… the “game” here is simply the game state and accepting messages to modify the state. It isn’t combined with the client code that sends those messages into the game, after prompting the human user however it’s going to do that. Currently in the Acquirex code, you can use IEx to call the functions that cause the messages to be sent.

Second Version

Armed with a bit more knowledge, let’s start over by generating a project with a supervision tree:

$ mix new connect_four --supAnd put it under version control:

$ git init

$ git add .

$ git commit -m "Initial commit of generated Elixir project with supervision tree"Now what? I suppose in a perfect world I would write some tests, but at the moment I have no idea what I would be testing. So let’s write some code instead and see what errors we get!

Here’s the generated ConnectFour module in lib/connect_four.ex:

defmodule ConnectFour do

use Application

# See http://elixir-lang.org/docs/stable/elixir/Application.html

# for more information on OTP Applications

def start(_type, _args) do

import Supervisor.Spec, warn: false

children = [

# Define workers and child supervisors to be supervised

# worker(ConnectFour.Worker, [arg1, arg2, arg3]),

]

# See http://elixir-lang.org/docs/stable/elixir/Supervisor.html

# for other strategies and supported options

opts = [strategy: :one_for_one, name: ConnectFour.Supervisor]

Supervisor.start_link(children, opts)

end

endGame

It looks like we should define some children. How about a Game?

diff --git a/lib/connect_four.ex b/lib/connect_four.ex

index f885f12..af57ebe 100644

--- a/lib/connect_four.ex

+++ b/lib/connect_four.ex

@@ -9,6 +9,7 @@ defmodule ConnectFour do

children = [

# Define workers and child supervisors to be supervised

# worker(ConnectFour.Worker, [arg1, arg2, arg3]),

+ worker(ConnectFour.Game, []),

]

# See http://elixir-lang.org/docs/stable/elixir/Supervisor.htmlIf you try to start this up right now, it will complain:

$ iex -S mix

Erlang/OTP 18 [erts-7.0.3] [source] [64-bit] [smp:8:8] [async-threads:10] [hipe] [kernel-poll:false] [dtrace]

Compiled lib/connect_four.ex

Generated connect_four app

=INFO REPORT==== 22-Oct-2015::10:05:01 ===

application: logger

exited: stopped

type: temporary

** (Mix) Could not start application connect_four: ConnectFour.start(:normal, []) returned an error: shutdown: failed to start child: ConnectFour.Game

** (EXIT) an exception was raised:

** (UndefinedFunctionError) undefined function: ConnectFour.Game.start_link/0 (module ConnectFour.Game is not available)

ConnectFour.Game.start_link()

(stdlib) supervisor.erl:343: :supervisor.do_start_child/2

(stdlib) supervisor.erl:326: :supervisor.start_children/3

(stdlib) supervisor.erl:292: :supervisor.init_children/2

(stdlib) gen_server.erl:328: :gen_server.init_it/6

(stdlib) proc_lib.erl:239: :proc_lib.init_p_do_apply/3You can see that it expects the ConnectFour.Game module to exist, and to have a start_link/0 function. If we had specified any arguments instead of the empty list [] then it would be looking for start_link/1 or start_link/2, etc., depending on how many arguments there were.

So now we need to define the module and function it’s looking for. Convention says that a module named ConnectFour.Game will go in a game.ex file in the lib/connect_four directory.

$ mkdir lib/connect_four

$ touch lib/connect_four/game.exWhat should it be? The Game will probably need to keep track of some sort of state, which means Agent is a possibility, but it will definitely need to receive messages like “Red player drops a game piece in column 3” – because of the messages, let’s go with GenServer.

In lib/connect_four/game.ex:

defmodule ConnectFour.Game do

use GenServer

@registered_name ConnectFourGame

def start_link do

GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, %{}, [name: @registered_name])

end

endGenServer is a module that abstracts the loop that holds the state as well as the receive loop that listens for messages. The parameters for the start_link function are:

- the name of the module that will contain the callbacks (this one –

__MODULE__is a macro that resolves at compile time to the name of the current module), - an empty Map for the initial state, and

- a list of configuration. In this case we’re registering the process with a name so we can find it later.

Now you should be able to start this up…

$ iex -S mix

Erlang/OTP 18 [erts-7.0.3] [source] [64-bit] [smp:8:8] [async-threads:10] [hipe] [kernel-poll:false] [dtrace]

Interactive Elixir (1.1.1) - press Ctrl+C to exit (type h() ENTER for help)

iex(1)>… and look at it in the observer:

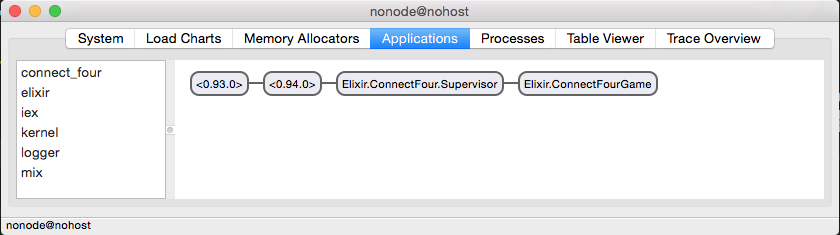

> :observer.start

:ok

Note that the registered name is displayed in the Observer. This comes from name: @registered_name (substituted as name: Elixir.ConnectFourGame at compile time). ConnectFourGame is an atom, and uppercase atoms automatically get an Elixir prefix.

CTRL-C twice to get out of IEx, and commit your changes.

$ git add . && git commit -m "Add Game module as GenServer"Board and Space

The next thing I’d like to do is print the board grid to make it easier to see the players’ moves. Well, that means we need a Board module, and probably some Spaces!

But first, how is this going to work? Let’s say you’ve started up the project in IEx. Maybe you’ll type ConnectFour.Game.print_board and expect to see the 7-by-6 grid. We’ll go with that for now.

Rather than representing the spaces as an array (or list), each space will be a process. Maybe in the future we’ll want to implement “Infinite Connect Four” which is not limited to six rows and seven columns. In that case, an array might not fit in memory. So the Board will need to keep track of the Spaces – that means it needs to be a Supervisor.

Create the files, again following the convention that the modules will be named ConnectFour.Board and ConnectFour.space and live in the connect_four directory as board.ex and space.ex.

$ touch lib/connect_four/board.ex

$ touch lib/connect_four/space.exNow comes a part that I probably would have gotten stuck on without Torben’s example.

Here is the Acquirex.Space.Supervisor (equivalent to our ConnectFour.Board): https://github.com/lehoff/acquirex/blob/master/lib/space_sup.ex

And here is the extended_all function that returns all of the row/column combinations: https://github.com/lehoff/acquirex/blob/master/lib/tiles.ex#L19

Curious about that question mark in extended_all? It returns the code point’s value for the character that follows. See http://stackoverflow.com/questions/26995608/what-does-do-in-elixir and http://elixir-lang.org/getting-started/binaries-strings-and-char-lists.html#utf-8-and-unicode.

The backtick ` is not anything special here– it’s simply the character that precedes a in the numerical list of character codes. In the Acquirex source code, the board was extended by one space on each side of the square, so columns a through i became columns ` through j.

The for ... <- ... do ... end syntax is a list comprehension. You may have used for loops in an imperative language, and in its simplest form, this is similar, (but it can do much more.)

Let’s start with a simple board that looks a lot like the game:

In lib/connect_four/board.ex:

defmodule ConnectFour.Board do

use Supervisor

@registered_name ConnectFourBoard

def start_link do

Supervisor.start_link(__MODULE__, [], [name: @registered_name])

end

endThe parameters for the start_link function are:

- the name of the module that will contain the callbacks (this one –

__MODULE__is a macro that resolves at compile time to the name of the current module), - an empty List for the parameters, (note that a Supervisor does not hold state,) and

- a List of configuration. Again we’re registering the process with a name so we can find it later.

Let’s add the Board to the list of workers in the top-level ConnectFour module

diff --git a/lib/connect_four.ex b/lib/connect_four.ex

index af57ebe..7a9ce86 100644

--- a/lib/connect_four.ex

+++ b/lib/connect_four.ex

@@ -10,6 +10,7 @@ defmodule ConnectFour do

# Define workers and child supervisors to be supervised

# worker(ConnectFour.Worker, [arg1, arg2, arg3]),

worker(ConnectFour.Game, []),

+ worker(ConnectFour.Board, []),

]

# See http://elixir-lang.org/docs/stable/elixir/Supervisor.htmlAnd try to start it up:

$ iex -S mix

Erlang/OTP 18 [erts-7.0.3] [source] [64-bit] [smp:8:8] [async-threads:10] [hipe] [kernel-poll:false] [dtrace]

lib/connect_four/board.ex:15: warning: undefined behaviour function init/1 (for behaviour :supervisor)

Compiled lib/connect_four/board.ex

Generated connect_four app

=INFO REPORT==== 22-Oct-2015::11:29:48 ===

application: logger

exited: stopped

type: temporary

** (Mix) Could not start application connect_four: ConnectFour.start(:normal, []) returned an error: shutdown: failed to start child: ConnectFour.Board

** (EXIT) an exception was raised:

** (UndefinedFunctionError) undefined function: ConnectFour.Board.init/1

(connect_four) ConnectFour.Board.init(:no_args)

(stdlib) supervisor.erl:272: :supervisor.init/1

(stdlib) gen_server.erl:328: :gen_server.init_it/6

(stdlib) proc_lib.erl:239: :proc_lib.init_p_do_apply/3Unlike with the GenServer, a Supervisor module with only a start_link function DOESN’T work. It expects to find an init/1 function that describes what needs to be supervised.

That’s because we’re using Supervisor.start_link/3 which says “To start the supervisor, the init/1 callback will be invoked in the given module.”

Here’s the full Board implementation, based on Torben’s Acquirex code.

In lib/connect_four/board.ex:

defmodule ConnectFour.Board do

use Supervisor

@registered_name ConnectFourBoard

@last_row 6

@last_column 7

def start_link do

Supervisor.start_link(__MODULE__, :no_args, [name: @registered_name])

end

def init(:no_args) do

children =

for t <- spaces do

worker(ConnectFour.Space, [t], id: t)

end

supervise(children, strategy: :one_for_one)

end

def spaces do

for row <- 1..@last_row, column <- 1..@last_column, do: {row, column}

end

endAnd try this again to see what errors we get.

$ iex -S mix

Erlang/OTP 18 [erts-7.0.3] [source] [64-bit] [smp:8:8] [async-threads:10] [hipe] [kernel-poll:false] [dtrace]

Compiled lib/connect_four.ex

Compiled lib/connect_four/board.ex

Generated connect_four app

=INFO REPORT==== 22-Oct-2015::10:19:33 ===

application: logger

exited: stopped

type: temporary

** (Mix) Could not start application connect_four: ConnectFour.start(:normal, []) returned an error: shutdown: failed to start child: ConnectFour.Board

** (EXIT) shutdown: failed to start child: {1, 1}

** (EXIT) an exception was raised:

** (UndefinedFunctionError) undefined function: ConnectFour.Space.start_link/1 (module ConnectFour.Space is not available)

ConnectFour.Space.start_link({1, 1})

(stdlib) supervisor.erl:343: :supervisor.do_start_child/2

(stdlib) supervisor.erl:326: :supervisor.start_children/3

(stdlib) supervisor.erl:292: :supervisor.init_children/2

(stdlib) gen_server.erl:328: :gen_server.init_it/6

(stdlib) proc_lib.erl:239: :proc_lib.init_p_do_apply/3

$See what’s happening? The overall Application ConnectFour couldn’t start because Board couldn’t start, and Board couldn’t start because there is no ConnectFour.Space module available with a start_link/1 function that expects a two-element tuple.

Let’s add the ConnectFour.Space module that is mentioned above, so that Board can create its workers and supervise them.

In lib/connect_four/space.ex:

defmodule ConnectFour.Space do

def start_link({row,column}) do

name = String.to_atom("R#{row}C#{column}")

Agent.start_link(fn -> Empty end, [name: name])

end

endThis will register a process for each Space as R1C1, R3C5, etc., up to R6C7. The name itself is arbitrary, but if you don’t name them something you can re-construct later, you’ll have a hard time finding them again to get and/or update the state. Also, each space starts out with a state of Empty.

Let’s explore this a bit in IEx:

$ iex -S mix

> ConnectFour.Board.spaces

[{1, 1}, {1, 2}, {1, 3}, {1, 4}, {1, 5}, {1, 6}, {1, 7}, {2, 1}, {2, 2}, {2, 3},

{2, 4}, {2, 5}, {2, 6}, {2, 7}, {3, 1}, {3, 2}, {3, 3}, {3, 4}, {3, 5}, {3, 6},

{3, 7}, {4, 1}, {4, 2}, {4, 3}, {4, 4}, {4, 5}, {4, 6}, {4, 7}, {5, 1}, {5, 2},

{5, 3}, {5, 4}, {5, 5}, {5, 6}, {5, 7}, {6, 1}, {6, 2}, {6, 3}, {6, 4}, {6, 5},

{6, 6}, {6, 7}]This is the result of the list comprehension that produces all the combinations of row and column. Each tuple is then passed in the call to ConnectFour.Space.start_link, and the row and column elements are used to construct the registered name for the Agent.

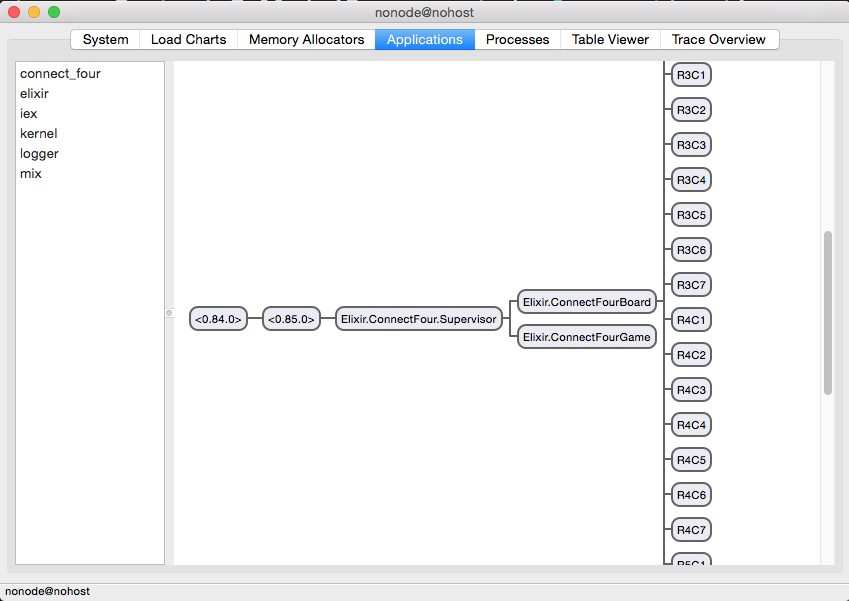

Take another look at the Applications tab in the Observer:

> :observer.start

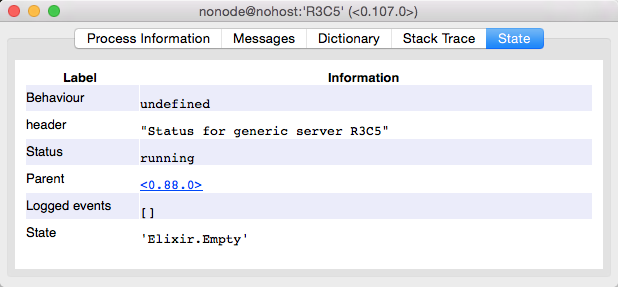

Now you can see the board and its list of children. Click on one of the nodes such as R3C5 and look at the State tab:

Here you can see that the state of this node is Elixir.Empty.

Go ahead and commit your changes.

$ git add . && git commit -m "Add Board and Space modules"Print Board Grid

Now that all the spaces are started under known registered names, we can find them again when we need them. Let’s print out the board grid. We said earlier we wanted to call ConnectFour.Game.print_board, so let’s add that function to the Game module:

diff --git a/lib/connect_four/game.ex b/lib/connect_four/game.ex

index 7a8bd81..ee6ff73 100644

--- a/lib/connect_four/game.ex

+++ b/lib/connect_four/game.ex

@@ -7,4 +7,8 @@ defmodule ConnectFour.Game do

GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, %{}, [name: @registered_name])

end

+ def print_board do

+ ConnectFour.Board.print

+ end

+

endWe’re delegating the printing to the Board itself.

In lib/connect_four/board.ex:

def print do

for row <- @last_row..1, do: print_columns(row) # 1

end

def print_columns(row) do

for col <- 1..@last_column, do: print_space(row,col) # 2

IO.write "\n"

end

def print_space(row, col) do

agent_name(row,col) # 3

|> Process.whereis # 4

|> Agent.get(fn x -> x end)

|> convert_for_display

|> IO.write

end

def convert_for_display(agent_state) do

case agent_state do

Empty -> "."

:red -> "R"

:black -> "B"

_ -> "?"

end

end

def agent_name(row,col) do

String.to_atom("R" <> Integer.to_string(row) <> "C" <> Integer.to_string(col) )

end# 1: I’m printing the rows in reverse, because when I worked on the logic for this last year I discovered that it’s easier to think of the bottom row as row #1. This will be clearer when we look at what happens during a player’s turn as they choose a column and drop a game piece into it.

# 2: For each row, we’ll print the columns left to right and then a linebreak.

# 3: For each space, we look up the agent by its registered name, get the state, and convert it to either “.”, “R”, “B” or ? for display.

# 4: Recall that the pipe operator |> sends the result of each line into the next as the first function parameter. The first two lines of print_space could be written as: Process.whereis( agent_name(row,col) ) (and in fact they originally were!)

And let’s see this in action:

$ iex -S mix

Erlang/OTP 18 [erts-7.0.3] [source] [64-bit] [smp:8:8] [async-threads:10] [hipe] [kernel-poll:false] [dtrace]

Compiled lib/connect_four/game.ex

Compiled lib/connect_four/board.ex

Generated connect_four app

Interactive Elixir (1.1.1) - press Ctrl+C to exit (type h() ENTER for help)

iex(1)> ConnectFour.Game.print_board

.......

.......

.......

.......

.......

.......

[:ok, :ok, :ok, :ok, :ok, :ok]

iex(2)>The dots indicate empty spaces. If there were red or black pieces they would be represented by R or B. (And if there is anything else in a space, a question mark will be displayed.)

Conclusion

This concludes Part 1 of Connect Four in Elixir. We’ve generated a project with a supervision tree and filled in the Game, Board and Space modules. Next we’ll see how to handle the players’ moves and update the board.

The code for this example is available at https://github.com/wsmoak/connect_four/tree/20151022 and is Apache licensed.

Copyright 2015 Wendy Smoak - This post first appeared on http://wsmoak.github.io and is CC BY-NC licensed.